News of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States' entering World War II came to most people directly or indirectly by radio. While the specifics of the date and location of the attack were a surprise, most Americans believed it was only a question of time before the country was drawn into this second global conflict and they were correct. Within the Winder family, James and brother-in-law, Philip Shaw were too old for military service so the major issues for the immigrant generation of Winders revolved around life on the home front, a more challenging experience than what they had experienced during World War I.

Trenton Evening Times - December 8, 1941

In 1941, the annual median income was $2000, almost exactly James Winder's income in 1939. James was 63 in 1941 and although it hasn't been confirmed, it appears he retired around 1943 when he turned 65. If so, he was one of the first group of Americans to receive social security. Retirement in 1943 might have been prudent as refrigerator manufacturing was one of the industries hardest hit by the shift to a wartime economy. Not long after Pearl Harbor, in March of 1942, James once again served as an honorary pall bearer for a pillar of Grace Church, Harry Klagg, Jr., Alf Blake was one of the "real" bearers." Even though in their 60's, James and wife, Mary, prepared to do their "bit" for the war effort as in August of 1942, they earned certificates to serve as air raid wardens.

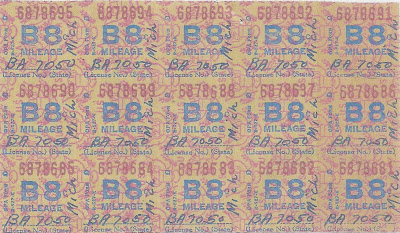

World War II gas ration stamps, courtesy of Paul Shubnell, as a postal worker, Paul's father was in the "B" category and entitled to additional gas beyond the basic ration

Other than one other article we will look at later, the two above references are the only times the Winders were mentioned in the newspapers during World War II. We can get still, however, get some sense of their war time lives by looking at the larger home front experience, especially rationing. Rationing began in 1942 and gradually placed major restrictions on almost every aspect of domestic life. Gasoline rationing (not to mention tire rationing) dramatically cut back automobile usage as drivers were placed in three different categories for which they would receive stamps authorizing them to purchase gasoline. This began with "A," the most limited allocation of four gallons a week (later cut to three) which at 15 miles per gallon allowed for an estimated 60 miles of driving per week. Categories "B" and "C" allocated additional gallons based on criteria like essential war work and specialized professions like doctors. Although this sounds fairly stringent, one study estimated that 50% of drivers were in the "B" and "C" categories.

World War II ration folder - courtesy of Paul Shubnell

How much any of this effected the Winders is unclear as we don't even know if they owned cars at this time. As city dwellers, they had access to public transportation, not to mention convenient railroad service to both New York and Philadelphia. Food rationing, however, was another matter and beginning in 1942 caused major changes in daily life. Early in May of 1942, all of the Winder families went to their local public schools to receive their ration books with sugar the first commodity to be restricted. Under an honor system, people were to disclose the amount of sugar on hand which was deducted from their initial allocation. At first ration coupons were good for a specific amount of sugar or other commodities, but in March of 1943 when rationing spread to processed foods, meat, cheese and other items, ration stamps began assigning point values to different products. Now home makers like Edith, Florence and Mary Ann had to budget not just dollars, but points. To further complicate matters, stamps were only valid during certain time periods so stores like A&P ran newspaper ads to help people keep track.

Trenton Evening Times - May 4, 1942

In order to encourage re-cycling, additional ration points were awarded for fats and oils that were returned to local butchers. Detailed instructions were also provided on saving and preparing cans so that the tin could be re-used. Families extended their food supplies through victory gardens, a government program that ultimately produced 40% of the nation's vegetables. Living in urban Trenton, it's not clear how much space the different Winder families had for gardens, but it was certainly limited. Even with supplemental food sources like victory gardens, families had to cut back on meals. The World War I innovation of meatless days was revived, usually Tuesdays and Fridays with cheese now rationed, eggs became a popular substitute.

Trenton Evening Times - March 25, 1943

Not surprisingly, rationing led to an active "black market," - a term first used in France in 1940. While the phrase suggests nefarious doings in dark alley ways, a "black market" transaction took place any time a commodity was sold for an amount over a price ceiling or was transferred without ration coupons. Accordingly such transactions were more common than we might think and it's not impossible the Winders occasionally partook. In the end as Richard Lingeman wrote in

Don't You Know There's a War On?, "Americans endured rationing for the rest of the war - grumbling, conniving, sacrificing and for the most part complying." Certainly the Winders experience in Trenton was easier than their British relatives where the ration was reportedly 2/3's that of the United States.

Perhaps one of the last surviving pictures of Mary Ann Hudson, adults pictured are Alice Walsh (Winder) and Mary Winder, the children are Peggy and Jim Walsh. Jim has just finished a day's work at the ship yards

Although James' generation was too old for military service, a number of their sons and sons-in-law did serve and fortunately all survived the war. There was, however, one death in the family during the war years as Mary Ann's long life ended on June 27, 1944. According to her obituary, she had been ill for some time which at 86 isn't surprising. Mary Ann lived an exceptional life. In England, she not only became a skilled china painter, but was a wife and mother, running a household with four children which she helped move 3000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean. After 20 years in her new country, helping her children reach adulthood, Mary Ann lost her husband when she was only 52 and lived another 34 years as a widow. Active in church and Eastern Star activities, not forgetting her family in England, Mary Ann was survived by 11 grandchildren and 12 great grandchildren, not to mention then unborn future generations who benefited from how she lived her life.

Trenton Evening Times - June 27, 1944

Mary Ann's death meant the breakup and sale of the house at 331 Rutherford Avenue which took place in June of 1945 at the end of World War II. Reportedly worth $4000 in 1940, the proceeds along with any other assets presumably were divided among her four children. Elsie for one needed some financial help as she would now be living on her own. Ultimately Elsie had an apartment at 10 West End Avenue in Trenton where she lived for the rest of her life. Elsie remained active in the Order of the Eastern Star and at St. Michael's Church where there is a memorial in her honor. As an elderly woman on her own in an urban area, Elsie had problems including minor injuries when struck by an automobile and as the victim of a robbery. She died on December 14, 1962 and is buried in the Riverview Cemetery, I believe in the family plot.

Trenton Evening Times - December 17, 1962

Elsie's death followed that of her two older siblings, James and Edith. Surviving his mother by only seven years, James died from cancer on April 22, 1951. His funeral was held at Grace/St. Paul's Church in Mercerville as the Grace congregation had moved out of Trenton. In addition to holding services at the funeral home, his Knights of Pythias brothers observed last rites at their next meeting. In addition to his wife and four daughters, James was survived by five grandchildren, a sixth grandchild was born after his death. James' wife, Mary died in 1954, she and James are buried in Ewing Church Cemetery, along with Alf and Hannah "Sis" Blake.

Trenton Evening Times - April 23, 1951

On April 16, 1955, about a year after Mary Winder's death, Edith Winder Shaw died of a heart attack at her home in Hamilton Township. Although Edith's name doesn't appear in a lot of newspaper articles, she was also apparently a member of Chapter 22 of the Order of the Eastern Star. Edith was pre-deceased by husband, Philip who died in 1949, they are buried in Colonial Memorial Park. At her death, her only surviving child was daughter, Edith Hartpence, as well as six grandchildren and five great grandchildren.

Trenton Evening Times - April 17, 1955

While it's not surprising that Florence, as the youngest sibling, lived the longest, and she out lived her siblings by almost a quarter of a century. Florence had been living with her son, Leonard, in Trenton, but died at Bayview Convalescent Home at the age of 96 on December 25, 1985. Sadly for a woman who had lost a husband and daughter to tragic accidents, she was also pre-deceased by another son, James William Winder Carr. In addition to Leonard, Florence was survived by sons, Leon, Earl, daughter, Mary Ann, 10 grandchildren, 10 great grandchildren and even one great-great-grandchild. Funeral services were held at the Broad Street Methodist Episcopal Church and her body was cremated. While I have no idea who was responsible, it's fitting the headline on her obituary includes the Winder name.

Trenton Evening Times - December 27, 1985